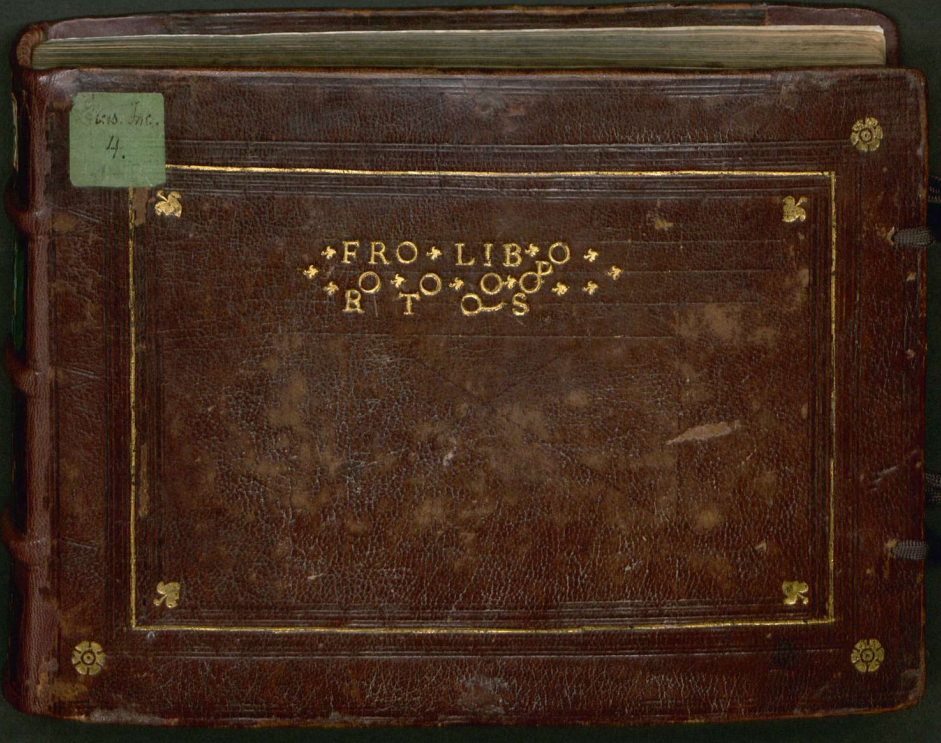

Petrucci’s Frottole, Vol. 1 for Lute and Voice

Available Now

Authors: Philip Horne; Matthew Royal

Publication date: 2021

Spiral-bound

$60

Free shipping to US addresses

Description

Frottole are Italian popular songs composed and performed in the last few decades of the 15th century in the north eastern region of the Italian peninsula near Venice. Queen Anna’s New World of Words or Dictionary…Collected and Newly Much Augmented by John Florio (1611) defines Frottole as: a countrie song, or roundelay, a wonton tale or skeltonicall riming. The verb form: frottoláre is defined as:to sing countrie songs or gigges, to tell wanton tales, to rime dogrel.

They are, in general, easy to sing pop songs with catchy hooks and melodic earworms reminiscent of early Phil Specter productions. They are generally easy to sing and easy to play and we thought they would make a good addition to the repertoire available to beginning and intermediate musicians like ourselves. Published here are an additional 63 high quality songs from the early 16th century to add to the standard madrigal repertoire.

The Frottole in book 1 are four voice song arrangements in the standard SATB format–though they are labeled: cantus, altus, tenor and bassus. The songs most often consist of many verses, the first of which is printed under the cantus with the rest of the text of the song printed as a poem below the tenor voice. The first verse under the cantus voice is not printed in a way that indicates which notes correspond to which syllables. Most of the time, we can say with relative certainty which line of verse corresponds to which musical section, but from there the assignment of text to note is at the singer’s discretion. In the other three voices, only the first few words of the first verse are printed under the musical material, offering us no idea whatsoever as to the assignment of note to text. There are exceptions to this rule, particularly if the song is intended to be performed vocally sans instrumental accompaniment.

Around 1450 Gutenberg perfected the art of printing text using moveable type. It took another 50 years before movable type was to be used effectively and commercially to print music. This innovation was the work of a printer working in Venice named Ottaviano Petrucci. His first printed book in 1501was the Odhecaton–a collection of Flemish and French chansons. Between 1501 and 1520 he printed a total of 61 books of music including 11 books of frottole, 9 of which are extant. These books of frottole, published between 1504 and 1509 contain approximately 450 Frottole. This book is a modern edition of the first volume, published in 1504.

Transcribing the Frottole for the modern performer.

In 1509 and 1511 Petrucci published two books of frottole arranged for lute and voice by Franciscus Bossinensis. We must take that as our starting point for arranging these frottole for lute and voice. Bossinensis’ arrangements are straightforward. The singer takes the cantus voice and the lute plays the tenor and bassus. He did not arrange the altus voice.

When we began the process of arranging the frottole for the lute we first arranged all three voices. It soon became clear that this was an impossible task. The tenor/bassus voices almost always fit natively on the lute; when the altus voice was added to the arrangement it often became unplayable, requiring fingerings that were either awkward or just plain impossible. In addition, the arrangements didn’t “sound” good with all three voices arranged. It became clear that only the tenor and bassus musical material should be included in the lute accompaniment.

While there are a few songs in the book that are clearly meant for four unaccompanied singers, we would maintain that these frottole arrangements are expressly written for lute accompaniment. During the course of performing/recording these songs, if we tried to transpose up or down to fit the singer’s voice, the transpositions did not fall natively on the lute or were not playable. Thus, the most straightforward lute arrangements were in the hexacord position in which they were published. And, as anyone can attest who has transcribed for the lute from vocal music of this era, the transcriptions often fall awkwardly on the instrument. Therefore, given that the majority of the frottole fall natively on the lute and that Bossinensis transcriptions are faithful lute arrangements of the tenor/bassus voices in the four part arrangements, and perhaps, that since the text is only printed under the cantus voice, it might be fair to conclude that these songs were written for lute and voice with the altus voice as additional instrumental or sung material to supplement the three part arrangement.

The first book of the frottole features the songs of the most well known frottole composers: Marchetto Cara and Bartolomeo Tromboncino. But the composer most represented is one who is identified variously as: Michael, Michael Pesentus Vero, Micha., Michaelis Cantus & verba, and Michaelis c & v. We cannot of course know whether these were different composers with similar names or the same person being referred to in different ways. First, the frottole by this composer are grouped together which would lead one to assume that they were by the same fellow. It would also be reasonable to assume that micha. is a shortened form of Michael and that perhaps there is a distinction being made between the songs in which Michael set others’ texts to music (MIchael, Michael Pesentus vero, and Micha.) and those in which he himself wrote both text and music (Michaelis canto & verbo). The first book contains 14 pieces by Tromboncino, 17 by Cara and 21 by Michael Pesentus Vero (assuming that those different names refer to the same composer).

Table of Contents

Antonius Capreolus Brixiensis

- Poi che per fede mancha

Bartholomeus Trumboncinus Vero

- Ah partiale e cruda morte

- Ala guerra ala guerra

- Benche amor mi faccia torto

- Crudel come mai potesti

- Deh p dio non mi far torto

- El convera chio mora

- Non val aqua al mio gran foco

- Piu che mai o suspiri fieri

- Poi che lalma p se molta

- Poi chel ciel contrario e ad.

- Scopri lingua el cieco ardore

- Se ben hor non scopro el foco

- Se mi e grato el tuo partire

- Vale diva mia va in pace

D. Antonio Rigum

- Donna ascolta el tuo amatore

Franciscus Anna Venetus

- Naqui al mondo p stentare

Georgius de la Porta vero

- Se me amasti quanto io te amo

Georgius Luppatus

- Voglio gir chiamado morte

Ioannes Brocchus Vero

- Alma suegliate hormai

- Alme che doglia e questa

Josquin Dascansio

- Inte domine speravi

Philippus de Lurano

- Se me e grato el tuo tornare

Marcus Cara Vero

- Chi me dara piu pace

- Come chel biancho cigno

- Defecerunt donna hormai

- Deh si deh no deh si

- Glie pur gionto el giorno aime

- Hor venduto ho la speranza

- In eterno io voglio amarte

- Io non compro piu sparanza

- La fortuna vol cossi

- Non e tempo daspectare

- O mia cieca e dura forte

- Oime el cor oime la testa

- Pieta cara signora

- Se de fede hor vengo ameno

- Se non hai perseueranza

- U dite voi sinestre

Micha.

- A dio signora a dio

- Aime chio moro

- Ben mille volte al di me dice

- In hospitas per alpes

- Integer vitea sceleris? purus

- Non mi doglio gia damore

- Passando per una rezolla

- Se in tutto hai destinato

- Trista e noiosa sorte

- Tu te lamenti atorto

- Una legiadra donna

- Vieni hormai non piu tard

Michael Pesentus Vero

- Ardo e bruscio e tu nol senti

- Alhor quando arivava

- Laqua vale al mio gran foco

Michaelis Cantus & Verba

- Fugir voglio el tuo bel volto

- O dio che la brunetta mia

- Poi chel ciel e la fortuna

- Questa e mia lho satta mi

- Sempre le come esser sole

- Si me piace el dolce foco

- Sio son stato aritornare